Explore Act of Sight: The Tsiaras Family Photography Collection

Show How the People Live

Established in New York City in 1936 by the photographers Sid Grossman and Sol Libsohn, the Photo League was a cooperative that offered instruction in photography and organized exhibitions, publications, and events. Many of the Photo League’s original members were raised in immigrant households, and the Great Depression was a defining experience for the group as a whole, informing its paired commitment to art photography and social change. In 1939, the photographer Margaret Bourke-White urged the cooperative to “show how the people live,” a phrase that aptly characterizes the work of such key Photo League practitioners as Libsohn, Lewis Hine, Aaron Siskind, Arthur Leipzig, Walter Rosenblum, and Helen Levitt, all of whom are represented in the Tsiaras Collection.

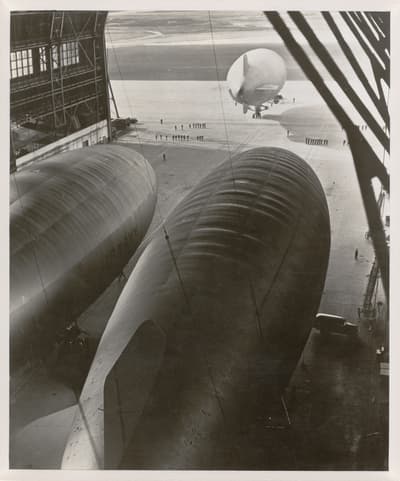

The Photo League remained active during World War II, and its members created enduring images during this period. Nonetheless, following the war, the U.S. attorney general added the cooperative to a list of organizations and people associated with “totalitarian, fascist, communist or subversive” activities, a claim based on the Photo League’s support of social causes and a history of ties to the Communist Party of America. Blacklisted photographers associated with the group were unable to find employment, and membership gradually declined. The Photo League closed its doors in 1951, yet its impact on how photography is taught and practiced reverberated for decades.

A Desire to Know

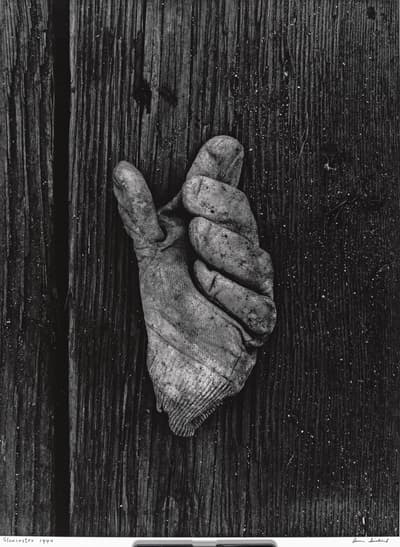

One of the Roosevelt administration’s New Deal initiatives, the Resettlement Administration was established in 1935 to address rural poverty. Renamed the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in 1937, the agency provided temporary housing for displaced farming families and migrants fleeing drought on the Great Plains. The economist Roy Stryker headed the FSA division that hired photographers and filmmakers to document rural hardship and life in the resettlement camps. “In this job and elsewhere,” Stryker later reflected, “I began to realize it was curiosity, it was a desire to know, it was the eye to see the significance around them. Very much what a journalist or a good artist is, is what I looked for.” The Tsiaras Collection features images by most of the FSA photographers, some of whom were also employed by the Works Progress Administration, which administered the Federal Art Project responsible for commissioning portrayals of workers and infrastructure projects in a modernizing United States.

In the commercial realm, documentary photographers were enlisted to promote industries and contribute to the expanding market for photo-illustrated magazines. The first issue of Life magazine was published in 1936 and featured a cover image of the Fort Peck Dam in Montana by Margaret Bourke-White, who earlier in the decade had photographed workers at the Lehigh Portland Cement facility. A group of photographers that included Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa joined forces in 1947 to establish Magnum Photos, an international collaborative that fed the growing demand for photographic realism.

Little America

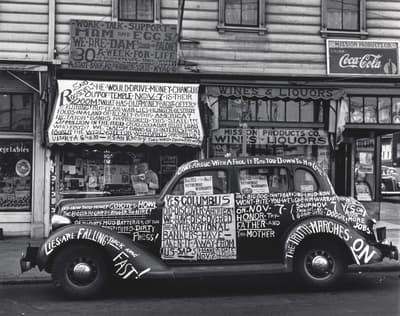

The phrase “Little America,” which appears on a road sign that David Vestal photographed in 1966, derives from the name of the U.S. exploration base on Antarctica. In the 1930s, hotels and other businesses catering to travelers in the American West adopted the name, which evoked a mythic notion of frontier living during an era of expansionism. In the context of this exhibition, the phrase applies to the ways that photographers have captured conceptions of American-ness, place by place, often through a focus on street life and byways.

“Get close enough to fill up the picture with what’s most important,” Vestal advised. “Get far enough away to include everything you need in the picture. What’s important? You decide. It’s your picture; you’re the photographer. No one else can say what’s important to you.” With these and other pragmatic instructions, he encouraged seasoned and aspiring photographers alike to explore a medium well suited to an ethos of individualism. Vestal demonstrated this approach through his extensive documentation of New York City and his perspective on a burgeoning American car culture. Streetscape patterns and brilliant sunlight defined Henry Wessel’s portrayal of the Southwest. And Lauren Greenfield considers the experience of women in the public sphere, a subject she has explored in the United States and beyond.

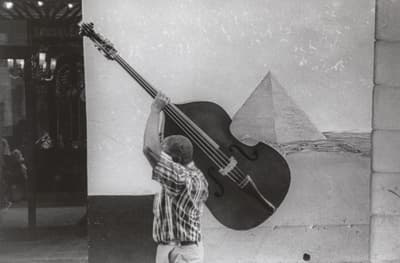

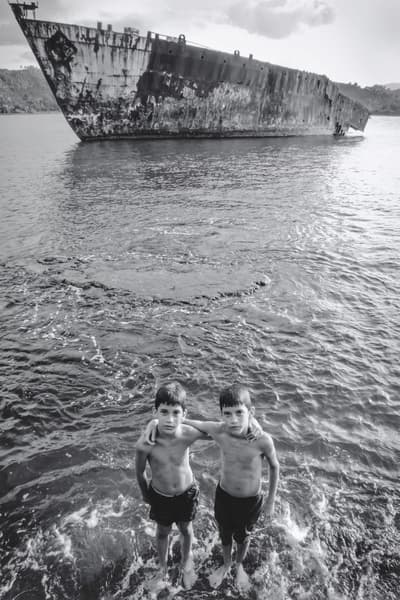

Exemplifying photography’s global reach, the collection also showcases American photographers working abroad in the context of their international peers.

Being Seen

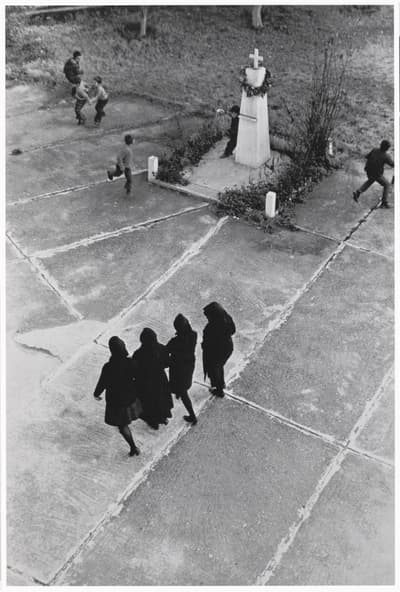

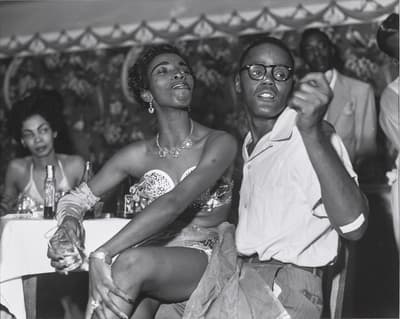

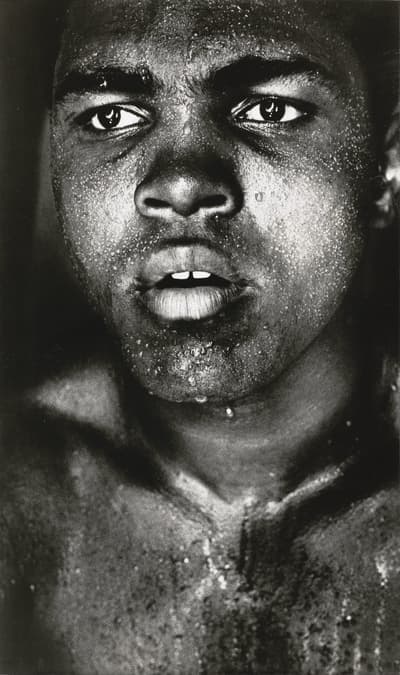

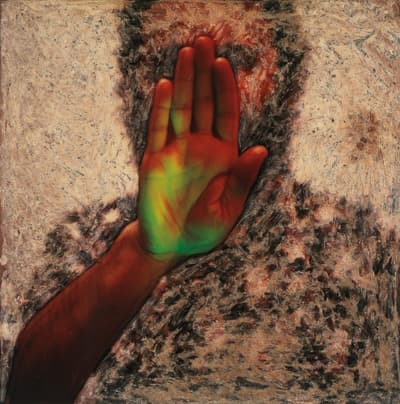

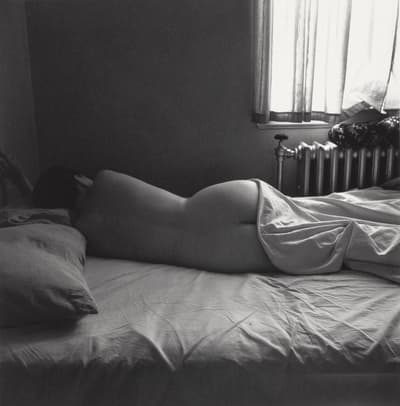

As an “act of sight,” photography is also an act of attention, however momentary. This section considers the “beings”—be they humans or animals, with others or alone—as seen by a photographer. Some of these subjects pose and perform for the camera in group or individual portraits. James Van Der Zee photographed costumed dancers during a pause in a dress rehearsal; Arnold Newman portrayed the artist Max Ernst engulfed in a cloud of smoke on a throne-like chair. And since the 1960s, Lucas Samaras has united portraiture with photographic manipulation, revealing seemingly infinite permutations of the self. Through this decades-long project, Samaras attests to being “my own critic, my own exciter, my own director, my own audience,” and he approaches his portraits of friends and fellow artists with the same spirit of playfulness and experimentation.

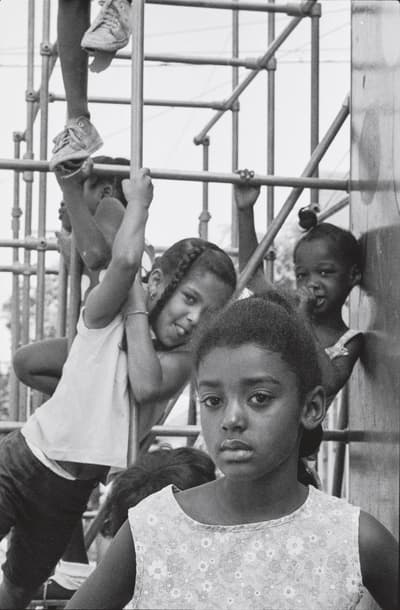

Other photographic encounters are comparatively serendipitous, as if seized upon at the moment the camera shutter opens and closes. Impromptu photo shoots emerge out of the synergies of street life, play, and recreation. Elliott Erwitt’s camera met the steely gaze of a chihuahua on a walk in New York City, and a playground jungle gym provided the backdrop for Roz Gerstein’s image of the self-possessed Shirla, age ten. In contrast, some subjects either are or appear to be oblivious to the photographer’s presence, creating the sense that we are witnessing a private view of the experiences of others. For instance, David Vestal photographed a father and a son sharing a moment of joyous connection.

Human-Altered Landscape

Friends in Photography

Pairings

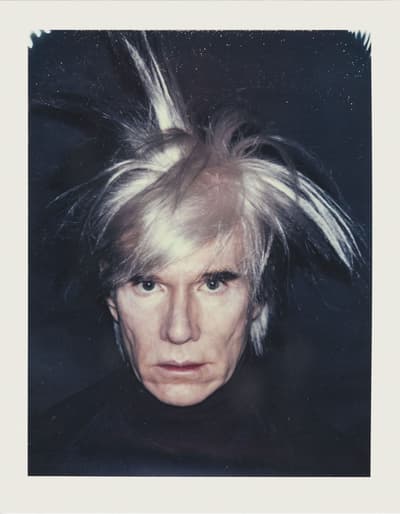

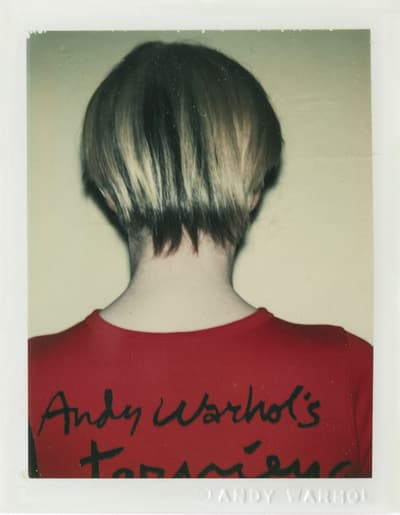

Ansel Adams maintained that in his photographs of nature, “There are always two people . . . the photographer and the viewer.” This section takes pairings as its point of departure, highlighting images of friends, couples, parents and their children, and people photographed in the context of their work or chosen vocation. The duo of Leda and the Swan represent a mythic pair, while several portraits, including two self-portraits by Andy Warhol, signal the enduring malleability of this very modern subject.