Explore Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948-1960

Archetypes/Stereotypes

In his early works, Lichtenstein evoked mythic narratives and archetypes, among them the warrior, the knight, and the outlaw (later the Pop art fighter pilot) as well as the mother and the damsel (later the Pop art “girl”). Such familiar tropes guided his appropriations from illustrated histories, art histories, and magazines, from which he teased out interrelated themes of selfhood and nationalism. Lichtenstein could veer, as his sources did, into the realm of the stereotype, even as his seeming modernist objectivity veiled something more personal at work. Early in the Pop art era, he observed that “the things that I have apparently parodied I actually admire,” indicating the push and pull between critique and identification at the heart of his project.

Stylistically unified and ambitious in scale, Lichtenstein’s pastels are distinct among his works. After 1949, he did not return to the medium, but what he accomplished in the two years dedicated to the series was consequential for his art. The pastels highlight types—the pilot, the cook, the diver—rendered in structured compositions and segmented shapes defined by distinct patches of color. Woman Knitting evokes a genre subject common in nineteenth-century American art, in which a seated female figure intent on a solitary task in a domestic environment was synonymous with defined family roles.

The painting that initiated this exhibition’s genesis, The Cowboy (Red), was a gift from Colby alumnus David W. Miller ’51, whose father acquired it from a gallery in New York in the 1950s, a time when Lichtenstein was living in Ohio but seeking exhibition opportunities across the US.

Representing archetypes and largely devoid of narrative content, this series of related works offered Lichtenstein opportunities to explore formal concerns and processes. At the same time, however, the artist’s use of abstraction and elimination of any individualism in the figures did nothing to confront established stereotypes of Indigenous North American cultures. This Eurocentric perspective promoted an association of Native Americans with the past, rather than with a contemporary living reality.

The Statesman is Lichtenstein’s playful take on the VIP of long ago. The figure’s red coat suggests he is British, joined by details—a patch of light blue, a decorated cuff, and a jaunty hand on hip—that create the impression of a specific type: the man in power. In 1964, Lichtenstein comically reduced this category to the generic Him, signifying a gentleman chosen for the perennial Who’s Who list.

Midwest Medieval

As he navigated his early career, Lichtenstein read books on the stages of an artist’s creative development, and children’s drawings informed his exploration of a purposefully naive or unschooled style. He also looked at images of the Bayeux Tapestry and made “medievalizing” works with a childlike quality; they conflate European kings and knights with Native American chiefs and warriors and the “founding fathers” of the United States.

The social and cultural backdrop for these antic jousts and spoofs on bravery was postwar America, which Lichtenstein experienced from the vantage point of the Midwest. Returning servicemen and the population surge of the baby boom era led to a renewed emphasis on traditional gender roles: women in the home, men in the workforce. The future Pop artist understood the situation as ripe for critique, even as he depicted himself, a new veteran, in the guise of an impish combatant well positioned to reap its rewards.

Although Lichtenstein executed a relatively small number of self-portraits during his long career, The Knight (Self-Portrait) was one of three completed between 1949 and 1952. For each, the artist employed a different stylistic approach and accordingly portrayed himself in a different persona. This painting shows Lichtenstein exploring his interest in the Middle Ages in comedic mode, imagining himself as a stocky knight, a clumsy, would-be hero whose impish smile and playfully rendered form belie his defensive stance with spear and shield raised.

This royal figure bears a striking resemblance to the figure in Lichtenstein’s painting Man on a Lion, while the crown of the king is echoed in the hat worn by George Washington in Lichtenstein’s two renditions of Washington Crossing the Delaware. Through such visual associations, Lichtenstein made connections within and between groups of works, just as he explored resonances and synergies between his various mediums.

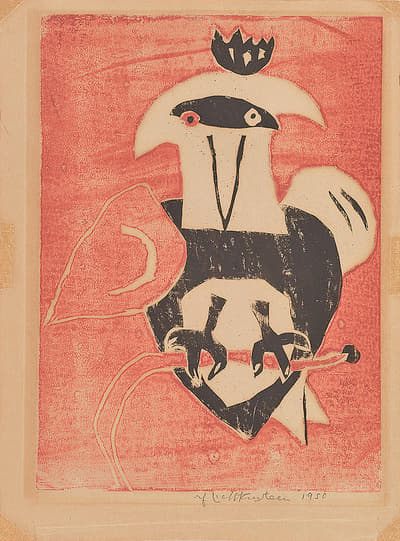

Birds were among the creatures that captured Lichtenstein’s attention early in his career. He drew and painted doves, parrots, and owls in the late 1940s. These works suggest Lichtenstein’s delight in the ways bird characteristics could be compared to such human tendencies as primping, posing, and showing off. Part of a series loosely based on works of medieval art, The Owl is rendered with a shield-like wing and a crown.

Among Lichtenstein’s earliest sculptures are whimsical constructions of repurposed metal objects combined with wood forms featuring areas of carving; The Horse sports a handle for a head and a latch for a tail.

Mythic America

In 1951, Lichtenstein began appropriating scenes from US history, for instance Revolutionary War battles, images of westward expansion, and Native American subjects. Many of these were taken from reproductions of nineteenth-century art found in popular sources. Satirizing US ideals that had become mythologized and enshrined, Lichtenstein explored modern styles, ranging from the intentionally childlike to the highly structured.

To many, the Allied victory in World War II and the country’s ascendance as a global superpower reinforced a belief in American exceptionalism—the idea that the United States is inherently distinct from and superior to other countries. By mining existing imagery from popular and print culture, Lichtenstein established the method of appropriation that would become a hallmark of Pop art, and in the process cast a critical eye on a widely accepted narrative.

Satirizing the American historical narrative was a central aim of Lichtenstein’s early work. Among the many established sources he drew upon during this period was Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 painting Washington Crossing the Delaware, a heroic depiction of Washington leading Continental Army troops in a frigid river crossing the night before the Battle of Trenton in 1776. Leutze’s work offered the perfect subject for the artist to lampoon because of its idealized portrayal of American history. The painting has hung in the Metropolitan Museum since the late nineteenth century, but Lichtenstein would have also known of printed sources, including the Album of American History (1944).

Lichtenstein’s Death of the General is based on Benjamin West’s well-known history painting The Death of General Wolfe (1770). Depicting a scene from the Seven Years’ War between the British and the French in which the English general James Wolfe was about to succumb to mortal wounds suffered in the Battle of Quebec, West rendered Wolfe as a Christ-like figure who had given his life in defense of the British colonies. The skeptical Lichtenstein found this melodramatic narrative an irresistible subject to parody, replacing the flag in West’s painting with a stylized version of the colonial-era American flag and rendering the dying general and surrounding figures in a faux-naive style.

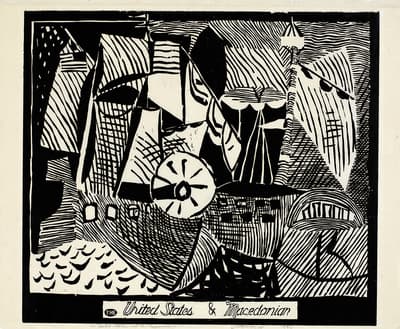

In the War of 1812, the USS United States captured the HMS Macedonian off the coast of Madeira and victoriously brought it to Newport, Rhode Island. In Lichtenstein’s rendition of the battle, the sails of the clashing vessels form a dense interplay of striped patterns, including that of the American flag in the upper left corner of the image. The cannon fire at the center of the composition evokes the wagon wheels found in the artist’s American West works.

Lichtenstein used an illustration of the Alfred Jacob Miller painting Interior of Fort Laramie (c. 1858–60) that appeared in “The Opening of the West,” an article in the July 4, 1949, issue of Life magazine as the source for his own painting titled Inside Fort Laramie (After Jabob MIller).

This portrait of the naval captain Stephen Decatur was based on an illustration in the Album of American History (1944), a series of books by the historian James Truslow Adams, who popularized the phrase “American dream.” During the War of 1812, Decatur was commander of the USS United States, a heavily armored frigate made famous by its victory against the HMS Macedonian in a battle off the coast of Madeira on October 25, 1812.

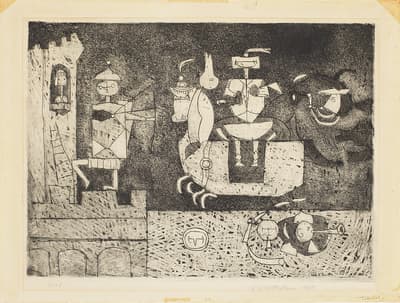

In the spring of 1943, a B-17 Flying Fortress nicknamed “Hell’s Angels”—after the title of a 1930 movie starring Jean Harlow—became the first USAAF heavy bomber to complete a combat tour of twenty-five missions over Europe. Lichtenstein’s rendition of the aircraft suggests a hybrid contraption—part machine, part horse—atop which sit two figures, one of whom brandishes a pistol like a cowboy. The motorcycle group Hells Angels was established in 1948, about five years before Lichtenstein created this work, but it does not appear to have been a reference for the artist here.

Painting Machines

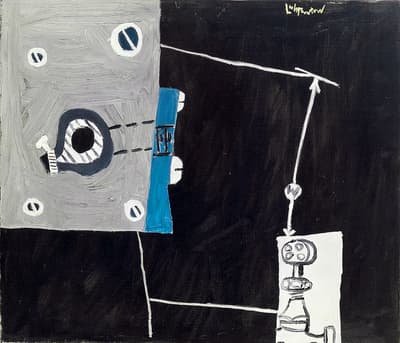

Around 1953, Lichtenstein embarked on a series of paintings depicting mechanical devices. These new works, unlike his earlier narrative scenes, were section diagrams showing the interiors of machines, gears, electronics, and blueprints. Pivoting away from his engagement with US history and folklore, these diagrammatic paintings anticipate some of Lichtenstein’s earliest Pop works. They focus on individual objects, emphasize drawing and design, and eliminate narrative content. Lichtenstein’s paintings of machines constitute only a small portion of his early works, but they underscore, through their banal subjects, the artist’s claim that he was more compelled by formal concerns than by subject matter. They also presage Lichtenstein’s interest in the mechanisms of printing, most notably his hand-painted Benday dots.

The inspiration for these paintings came from at least two sources. An engineering drawing class at the Ohio State University had exposed Lichtenstein to A Manual of Engineering Drawing, an illustrated reference book for mechanical drafting. Additionally, while making these paintings he was working odd jobs, including painting the black-and-white faces of dials and meters at the Hickok Electrical Instrument Company in Cleveland.

Mechanism, Cross Section is the largest work in Lichtenstein’s series on mechanical devices. These diagrammatic paintings and drawings marked a departure from the historical subjects of the previous years. Lichtenstein was likely attracted to the schematic nature of these mechanisms, and their emphasis on drawing and design anticipates some of his earliest Pop works, in which the artist rendered single objects.

Cosmic Abstraction

By the late 1950s, as Lichtenstein searched for a distinctive style, his work became increasingly abstract. Like many artists of his time, he felt obliged to experiment with Abstract Expressionism, a gestural mode of painting that had been the dominant aesthetic for nearly a decade. Yet in the process, he invented a groundbreaking technique that involved painting with multiple bright hues simultaneously: A cloth loaded up with stripes of brilliantly colored paint became a substitute for the painter’s brush. Lichtenstein at once partially removed the artist’s hand from the process, parodied the seriousness and self-consciousness of Abstract Expressionism, and established what would become his trademark palette of saturated primary colors. In a single gesture, both literal and metaphorical, he repudiated his predecessors while establishing a fundamental element of his Pop vocabulary. These lyrical abstractions inspired a series of Pop brushstroke paintings in the mid-1960s, a subject to which Lichtenstein would repeatedly return over the next three decades.

In 1960, not long before his turn toward Pop art the following year, Lichtenstein’s abstract paintings became increasingly filled with a quilt-like patchwork of colorful blocky brushstrokes. He continued to refine the technique of painting with multiple colors simultaneously by dragging a rag across the canvas. The two untitled paintings depicted above represent the culmination of the artist’s experiments with abstraction.

Composition belongs to a small group of assemblages—part painting, part sculpture—that Lichtenstein created in the mid-1950s. It suggests a figure whose “body” is represented in pink and red paint, its “face” a collection of blue stripes topped by a blue headband. Picasso’s Guitar was a source for Lichtenstein, as were painted and carved totem poles, which document the family lineages among Native peoples in North America’s Pacific Northwest. Lichtenstein drew upon this visual language to fuel his exploration of abstraction.

Drawing was central to Lichtenstein’s artistic practice, and he continued to make both small sketches and larger, finished works on paper throughout the late 1950s. These works, though not necessarily direct studies for larger paintings, as was the case earlier in the decade, were an important part of his process. In Untitled (1959) and related watercolors, Lichtenstein experimented with applying multiple colors simultaneously.

By 1960, Lichtenstein had developed the aforementioned experimental painting technique of using a rag to apply several colors simultaneously to the canvas with one sweeping gesture. He also increasingly employed a palette of bright primary colors, which he would soon adopt for his Pop work.

In Variations No. 7, the artist combines the frenetic brushstrokes seen in his work from 1957–58 with small bands of color painted in stripes. This painting shows Lichtenstein transitioning out of his brief period working in an expressionistic representational manner and moving toward complete abstraction.

Glimmers of Pop

In 1958, Lichtenstein produced a series of drawings featuring the Disney cartoon characters Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck and Warner Bros.’ Bugs Bunny. First introduced in short animated films in the late 1920s and 1930s, these anthropomorphized animals—easygoing Mickey, irascible Donald, braggart Bugs—were part of a broader universe of fictional creatures whose predecessors included Peter Rabbit in the UK and Krazy Kat in the United States.

By the mid-twentieth century, Disney’s and Warner’s creations had become prime exports of US culture. Their prominence made them obvious candidates for Lichtenstein’s consideration, given his abiding interest in popular content. He rendered each of the three famous figures in loose gestures that resonated with his concurrently emerging abstractions. In addition to drawings, Lichtenstein also made semi-abstract paintings of cartoon characters, which he later recalled using as canvas drop cloths when creating the works now known as his earliest contributions to Pop art.

The Explorer is an early example of Lichtenstein’s appropriation of imagery from popular print culture, a process that would become a hallmark of Pop art. Taken from a nineteenth-century advertisement for canned corned beef, this image depicts an intrepid adventurer and his trusty dog cheerfully trekking through the mountainous West. By including the brand name Libby, McNeil & Libby, along with the slogan that the company’s cooked corned beef “is valuable for explorers and travelers,” the artist satirizes the often idealized depictions of westward expansion in a painting that prefigures Pop art’s interest in consumerism and consumer culture.

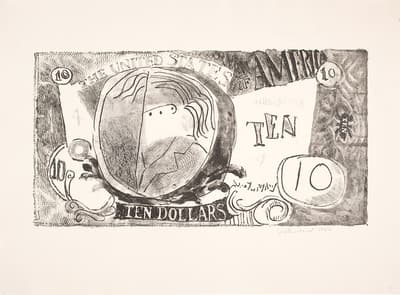

Reflecting on Ten Dollar Bill [Ten Dollars], Lichtenstein wryly commented, “The idea of counterfeiting money always occurs to you when you do lithography.” His representation of the ten-dollar bill features a bird-like Alexander Hamilton that distantly echoes John Trumbull’s 1805 portrait of the American statesman, the source for the image on the current ten-dollar bill that was introduced into circulation in 1928. Another reference is the hyperrealistic or “trompe l’oeil" paintings of currency popular during the nineteenth century.

Untitled (c. 1958), a drawing from around the same year, suggests the close association between Lichtenstein’s cartoon subjects and some of his abstractions, as if an animated character might emerge from this dynamic assembly of gestures and marks.

Lichtenstein’s loosely rendered drawings of cartoon characters, including Mickey Mouse I, were the precursors to Look Mickey (1961), often credited as the first Pop painting. His interest in Americana as well as a fascination with the “VIP” were central to his motivations for producing these works. He may have also created them to please and entertain his young children, and this charming story is now a Pop art legend.

Paul Bunyan, an early drawing of an imaginary forest scene, is arguably the first known example of the appropriation and adaptation of popular sources that would come to be synonymous with Lichtenstein’s art. The folk hero of tales long recounted by loggers on cold winter nights, Paul Bunyan rose to national attention in the early twentieth century, when he became the mascot of the Minnesota-based Red River Lumber Company, which widely distributed promotional pamphlets featuring accounts of his extraordinary skill at felling trees.

Sighting Sources

Lichtenstein was an avid museumgoer, but the sources he explored in his studio came from mainstream printed matter: books, magazines, and, most famously, comic books. The Colby Museum’s presentation of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making includes a gallery dedicated to a selection of the artist’s printed source materials and related artworks, shown together with works from the Colby Museum collection that exemplify his early-career visual interests. In some instances, Lichtenstein cited his sources in his paintings’ titles, but more often he adapted and transformed these and other references as he worked them into his paintings.

In 1937, at the age of fourteen, the future Pop artist received his first art book, Thomas Craven’s Modern Art: The Men, the Movements, the Meaning (1934), a volume whose subtitle captures both the author’s authoritative style and the limits of his worldview. A copy of this volume appears in this section of the exhibition. Craven advised American artists to gain independence from European models by representing authentic American subjects that reflected distinct regional differences. With characteristic skepticism, Lichtenstein viewed regionalism as one possible conceptual and stylistic gesture to be made in response to the country’s growing global artistic recognition.

Lichtenstein looked at nostalgic depictions of the American West for a series of works in the early 1950s, nearly a century after Alfred Jacob Miller painted Buffalo Hunt with Lances. The future Pop artist’s preferred sources were printed representations of paintings such as this, which he found in popular publications like Life magazine. The presence of these images in mainstream media signaled an enduring, and arguably newly reinforced, belief in a false narrative of extinction that glossed over the brutal reality of settler colonialism and overlooked the contemporary reality of Native Americans living in the United States.

Lichtenstein’s contemporary Jack Levine was known for his satirical paintings of modern life. Rather than mining history, he transformed present-day figures into caricatures so that they came to embody standard “types.” Politicians were among Levine’s most frequent subjects. The identity of the subject for The Senator is unknown, but he resembles Karl E. Mundt, a Republican from South Dakota who chaired the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations for the Army-McCarthy Hearings in 1954.

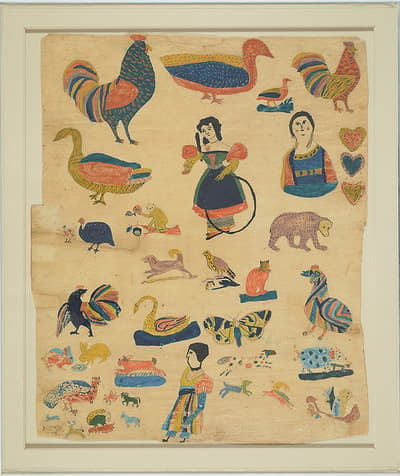

Lichtenstein read books on the phases of artistic development that featured children’s drawings, and many of his works from the early 1950s are purposefully naive or childlike in style, an approach he shared with other modernists. And like the young unknown artist of Watercolor Done by a Child, he was interested in birds as subjects. Lichtenstein’s parrots, doves, and owls are creatures akin to the winged beings in this delightful menagerie.

Born in the Louvre Palace during the French Revolution, Horace Vernet grew up to paint for the Bourbon Restoration and was best known for his battle scenes. As a young artist, he rejected the dominant style of classicism—or depicting subjects in a stylized manner to evoke ancient Greece and Rome—in favor of realistic detail.

A Row of Cavalrymen On Horseback: a Study for “La Prise De La Smalah D'abd-El-KaI" was one of many oil sketches Vernet produced while working on a painting designed to glorify the military exploits of King Louis-Philippe, in this case a battle won by his son, the Duke of Aumale, at Taguin, south of Algiers. Vernet’s battle scenes were not a source of imagery for Lichtenstein, but the French artist’s attention to modes of dress is resonant with Lichtenstein’s investigation of style conventions from this period.

Installation Views

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers

Installation view of Roy Lichtenstein: History in the Making, 1948–1960, Upper and Lower Jetté Galleries, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 2021. Photo: Luc Demers