By Carl Little

Gertrude Abercrombie (1909-1977) lived a nonconforming life, one that at times overshadowed her work as a painter. Nicknamed Queen of the Bohemian Artists in her home city of Chicago, Abercrombie hung out with such jazz greats as Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, and Sarah Vaughan, and cultivated an eccentric persona that included being a witch. She even gained renown for the way she walked, an animated step that inspired “Gertrude’s Bounce” by jazz pianist Richie Powell.

While acknowledging her unconventional biography, Gertrude Abercrombie: The Whole World Is a Mystery at the Colby College Museum of Art focuses on her artwork. With more than 80 paintings, this traveling exhibition, with its expansive catalogue, does more than simply revive interest in an underappreciated artist: it carves out an enduring place for Abercrombie in the pantheon of American art history.

“The Colby College Museum of Art is interested in interrogating the definition of what American art is,” said Sarah Humphreville, the Lunder Curator of American Art and co-curator of the Abercrombie show. To that end, it revisits “the canon” to identify what has been neglected within that art-historical overview. If Abercrombie was well known in Chicago and the Midwest more broadly, the rest of the world, Humphreville noted, “wasn’t tuned in.”

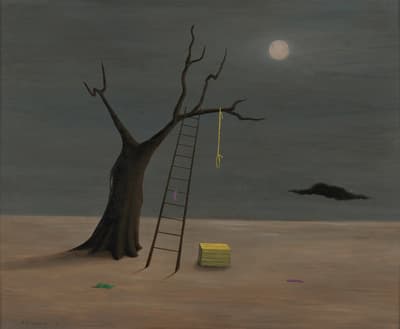

Abercrombie’s paintings feature dream-like scenarios, bleak landscapes with crescent moons, bare trees, and lone female figures, often dressed in black (some bring to mind Morticia Addams). Interiors are equally spare, with a table the sole furnishing. There are cats and owls, underscoring the witch image. Still lifes feature shells, wish bones, dominoes, and eggs. The self-portraits generally offer a rather severe, unsmiling visage. The work in general displays, in Humphreville’s words, “a very deep sense of unease.”

Abercrombie encountered René Magritte’s work in the mid-1950s and felt an artistic kinship, going so far as to refer to him as her “spiritual daddy.” While it recalls some of the Belgian surrealist’s canvases, A Picture in a Picture in a Picture, 1955, offers a painting-within-a-painting conceit that the artist started using early in her career in canvases such as White Cat, ca. 1938, Letter to Karl, 1940, and The Past and the Present, ca. 1945. Curiously, she attributed her use of this mise en abîme device to Quaker Oats ads: “There was always a picture of the man and then another picture of the man behind him, and then another one and another one,” she told famed radio broadcaster and historian Studs Terkel in a 1977 interview.